February-March 1864:

First State Color, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers; carried during the Red River Campaign across Louisiana, March-May 1864.

On February 25 and March 1, 1864, members of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry set off for a phase of service in which their regiment will truly make history. Steaming for New Orleans aboard the Charles Thomas, the men of the 47th arrive at Algiers, Louisiana on or after February 28, and are then shipped by train to Brashear City. Following another steamer ride—this time to Franklin via the Bayou Teche—the 47th joins the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps. In short order, the 47th becomes the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks. The 1st Division of the U.S. Army’s 19th Corps is commanded by Brigadier-General William Hemsley Emory. The 2nd Brigade is led by Brigadier-General James W. McMillan.

From March 14-26, the 47th marches through New Iberia, Vermillionville, Opelousas, and Washington while en route to Alexandria and Natchitoches. Often short on food and water, a number of men from the regiment become ill during the grueling marches in the harsh Louisiana climate while others are felled by dysentery and/or tropical diseases.

April 6, 1864:

Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks sends his Union troops west via a single road. The column of men stretches for twenty-plus miles.

Heading the column are roughly four thousand cavalrymen led by Brigadier-General Albert Lindley Lee. Most are newbies who have little experience on horseback. They are followed by three hundred supply wagons, artillery units, one infantry division, seven hundred additional support wagons, and most of the 13th and 19th Corps.

As they move, they move west, marching toward Los Adaes, Louisiana, and then north on the Shreveport-Natchitoches stagecoach road. The column is SO long and SO slow moving that the troops at its head reach Pleasant Hill before the last men have even left Natchitoches, Louisiana.

April 7, 1864:

Union cavalry troops of Major-General Nathaniel Banks begin their march. Led by Brigadier-General Albert Lee, their progress is slowed by Union wagons. Lee’s requests for infantry support plus redirection of the wagons is denied by Banks and leaders of the U.S. Army’s 19th Corps.

April 8, 1864 (morning):

Union Major-General Nathaniel Banks’ Cavalry, led by Brigadier-General Albert Lee, crosses a stream, and moves through trees and fields. In the distance, atop a ridge, Lee spots Confederate cavalry and infantry which stretch along both sides of the road for three quarters of a mile. After he spots more Confederate cavalry troops to his right, he asks for help from Banks. After taking his time, Banks finally orders the 13th U.S. Army to move up to assist Lee’s cavalry. Banks also moves up to see what’s happening.

Arrayed before him in the distance are roughly ten thousand troops led by Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor, a plantation owner and son of former U.S. President Zachary Taylor. (Ironically, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had just spent a significant period of time—off and on between 1862 to early 1864—garrisoning Fort Zachary Taylor in Key West, Florida.)

It’s the morning of April 8, 1864, the day of the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads near Mansfield, Louisiana.

Confederate Taylor and his 10,000 troops expect Banks’ Union forces to charge—but they don’t. A six-hour waiting game ensues.

April 8, 1864 (afternoon and evening):

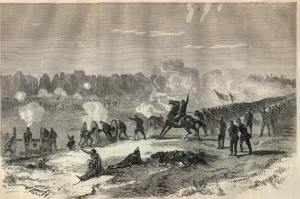

At 4 p.m. Louisiana time, Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor’s left flank slowly begins an echelon formation attack on troops commanded by Union Major-General Nathaniel Banks, and the Union’s cavalry line buckles. BUT, in the process, eleven out of fourteen Confederate officers are killed in action within fourteen minutes of the opening charge.

Replacing one of those fallen Confederate leaders is Brigadier-General Camille Armand Jules Marie, the Prince de Polignac. A Prince of France, he fought with the Confederate Army during America’s Civil War, and is an important name for descendants of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and others studying the 47th’s history because, later that same day, forces led by Polignac and Confederate Brigadier-General Thomas Green (Texas Cavalry Corps) directly engage in battle with the 47th Pennsylvania.

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers are led by Colonel Tilghman H. Good, the regiment’s founder, and his second in command, Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander.

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers are led by Colonel Tilghman H. Good, the regiment’s founder, and his second in command, Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander.

Following the charge by Taylor’s Confederate troops and the resulting buckling of the Union’s right flank, Banks’ left Union flank also collapses. Taylor’s troops continue on, puncturing a secondary Union position mile three quarters of a mile behind the Union’s front line.

Banks then orders Brigadier-General William Emory to move his 1st Division, 19th U.S. Army Corps men to the front. Among Emory’s 5,859 men were nine New York regiments, three from Maine—and the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers. Ninety minutes and seven miles of marching later, Emory’s men are waiting for the Confederates on the ridge above Chapman’s Bayou.

* Note: The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were positioned behind the 161st New York, 29th Maine, and other Union regiments at or near the farm of Joshua Chapman, about five miles southeast of Mansfield, Louisiana. The battles here were termed the “Peach Orchard” fight by Confederates and “Pleasant Grove” by 47th Pennsylvanians, a name attributed by some historians to the live oak trees in front of Chapman’s house. The fighting at the peach orchard was particularly brutal.

19th U.S. Army Map, Phase 3, Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield, Louisiana (April 8, 1864, public domain).

As Confederates, led by Polignac, et. al. attack the center of the Union line, the 161st buckles, but the 29th Maine is able to repulse the Confederates. Green’s Confederate cavalrymen then attempt an end run on the Union’s right flank. His troops include: Brigadier-General Xavier DeBray’s Cavalry Brigade (composed of the 26th and 36th Texas Cavalry) and Colonel Augustus Buchel’s Cavalry Brigade (composed of the 1st Texas Cavalry and Terrell’s Texas Cavalry).

Initially positioned to the right of the 13th Maine Infantry, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and 13th Maine both pinwheel to head off Green’s attack, and end Green’s flanking effort.

As darkness falls on April 8, 1864, fighting wanes and then ceases as exhausted troops on both sides collapse between the bodies of their dead comrades. Seventy-four men were killed in action, at least one hundred and sixty-one are wounded, and hundreds more are declared missing in action, including one hundred and eighty-eight men from the 19th U.S. Army (to which the 47th Pennsylvania was attached). Some of these missing soldiers (including members of the 47th Pennsylvania) are eventually found wounded or dead; others (including 47th Pennsylvanians) end up as prisoners of war (POWs), at Camp Ford, a Confederate prison near Tyler, Texas, but some remain missing to this day.

* Note: Some historians believe that these missing men may have been hastily interred somewhere on or near the battlefield by fellow soldiers or local residents, but no remains were found during archaeological excavations of the area during the late 20th and early 21st centuries. In 1996, L.P. Hecht, in his Echoes from the Letters of a Civil War Surgeon, reported that wild hogs had eaten the remains of at least some of the federal soldiers who had been left unburied.

April 8, 1864 (late evening):

Receiving word of another likely attack, Banks orders his Union troops to withdraw to Pleasant Hill (not to be confused with the aforementioned Pleasant Grove). This withdrawal commences after midnight and through the early hours of April 9, 1864. According to Banks:

From Pleasant Grove, where this action occurred, to Pleasant Hill was 15 miles. It was certain that the enemy, who was within the reach of re-enforcements, would renew the attack in the morning, and it was wholly uncertain whether the command of General Smith could reach the position we held in season for a second engagement. For this reason the army toward morning fell back to Pleasant Hill, General Emory covering the rear, burying the dead, bringing off the wounded, and all the material of the army. It arrived there at 8.30 on the morning of the 9th, effecting a junction with the forces of General Smith and the colored brigade under Colonel Dickey, which had reached that point the evening previous.

* To view the abridged casualty lists from the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads, visit “Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield, Louisiana, 8 April 1864 — Casualties and POWs from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.”

April 9, 1864 (morning):

Arriving at Pleasant Hill, Louisiana around 8:30 a.m., and with the enemy believed to be in pursuit, Union Major-General Nathaniel Banks orders his troops to regroup and ready themselves for a new round of fighting.

The Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana is just hours from its start. In his official Red River Campaign Report penned a year later, Banks described how the day unfolded:

A line of battle was formed in the following order: First Brigade, Nineteenth Corps, on the right, resting on a ravine; Second Brigade in the center, and Third Brigade on the left. The center was strengthened by a brigade of General Smith’s forces, whose main force was held in reserve. The enemy moved toward our right flank. The Second Brigade [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers] withdrew from the center to the support of the First Brigade. The brigade in support of the center moved up into position, and another of General Smith’s brigades was posted to the extreme left position on the hill, in echelon to the rear of the left main line.

Light skirmishing occurred during the afternoon. Between 4 and 5 o’clock it increased in vigor, and about 5 p.m., when it appeared to have nearly ceased, the enemy drove in our skirmishers and attacked in force, his first onset being against the left. He advanced in two oblique lines, extending well over toward the right of the Third Brigade, Nineteenth Corps. After a determined resistance this part of the line gave way and went slowly back to the reserves. The First and Second Brigades were soon enveloped in front, right, and rear. By skillful movements of General Emory the flanks of the two brigades, now bearing the brunt of the battle, were covered. The enemy pursued the brigades, passing the left and center, until he approached the reserves under General Smith, when he was met by a charge led by General Mower and checked. The whole of the reserves were now ordered up, and in turn we drove the enemy, continuing the pursuit until night compelled us to halt.

The battle of the 9th was desperate and sanguinary. The defeat of the enemy was complete, and his loss in officers and men more than double that sustained by our forces. There was nothing in the immediate position or condition of the two armies to prevent a forward movement the next morning, and orders were given to prepare for an advance. The train, which had been turned to the rear on the day of the battle, was ordered to reform and advance at daybreak. I communicated this purpose at the close of the day to General A. J. Smith, who expressed his concurrence therein. But representations subsequently received from General Franklin and all the general officers of the Nineteenth Corps, as to the condition of their respective commands for immediate active operations against the enemy, caused a suspension of this order, and a conference of the general officers was held in the evening, in which it was determined, upon the urgent recommendation of all the general officers above named, and with the acquiescence of General Smith, to retire upon Grand Ecore the following day. The reasons urged for this course by the officers commanding the Nineteenth and Thirteenth Corps were, first, that the absence of water made it absolutely necessary to advance or retire without delay. General Emory’s command [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers] had been without rations for two days, and the train, which had been turned to the rear during the battle, could not be put in condition to move forward upon the single road through dense woods, in which it stood, without difficulty and loss of time. It was for the purpose of communicating with the fleet at Springfield Landing from the Sabine Cross-Roads to the river, as well as to prevent the concentration of the Texan troops with the enemy at Mansfield, that we had pushed for the early occupation of that point. Considering the difficulty with which the gun-boats passed Alexandria and Grand Ecore, there was every reason to believe that the navigation of the river would be found impracticable. A squadron of cavalry, under direction of Mr. Young, who had formerly been employed in the surveys of this country and was now connected with the engineer department, which had been sent upon a reconnaissance to the river, returned to Pleasant Hill on the day of the battle with the report that they had not been able to discover the fleet nor learn from the people its passage up the river. (The report of General T. Kilby Smith, commanding the river forces, states that the fleet did not arrive at Loggy Bayou until 2 p.m. on the 10th of April, two days after the battle at Sabine Cross-Roads.) This led to the belief that the low water had prevented the advance of the fleet. The condition of the river, which had been steadily falling since our march from Alexandria, rendered it very doubtful, if the fleet ascended the river, whether it could return from any intermediate point, and probable, if not certain, that if it reached Shreveport it would never escape without a rise of the river, of which all hopes began to fail. The forces designated for this campaign numbered 42,000 men. Less than half that number was actually available for service against the enemy during its progress.

The distance which separated General Steele’s command from the line of our operations (nearly 200 miles) rendered his movements of little moment to us or to the enemy, and reduced the strength of the fighting column to the extent of his force, which was expected to be from 10,000 to 15,000 men. The depot at Alexandria, made necessary by the impracticable navigation, withdrew from our forces 3,000 men under General Grover. The return of the Marine Brigade to the defense of the Mississippi, upon the demand of Major-General McPherson, and which could not pass Alexandria without its steamers nor move by land for want of land transportation, made a further reduction of 3,000 men. The protection of the fleet of transports against the enemy on both sides of the river made it necessary for General A. J. Smith to detach General T. Kilby Smith’s division of 2,500 men from the main body for that duty. The army train required a guard of 500 men. These several detachments, which it was impossible to avoid, and the distance of General Steele’s command, which it was not in my power to correct, reduced the number of troops that we were able at any point to bring into action from 42,000 men to about 20,000. The losses sustained in the very severe battles of the 7th, 8th, and 9th of April amounted to about 3,969 men, and necessarily reduced our active forces to that extent.

The enemy, superior to us in numbers in the outset, by falling back was able to recover from his great losses by means of re-enforcements, which were within his reach as he approached his base of operations, while we were growing weaker as we departed from ours. We had fought the battle at Pleasant Hill with about 15,000 against 22,000 men and won a victory, which for these reasons we were unable to follow up. Other considerations connected with the actual military condition of affairs afforded additional reasons for the course recommended. Between the commencement of the expedition and the battle of Pleasant Hill a change had occurred in the general command of the army, which caused a modification of my instructions in regard to this expedition.

Lieutenant-General Grant, in a dispatch dated the 15th March, which I received on the 27th March, at Alexandria, eight days before we reached Grand Ecore, by special messenger, gave me the following instructions:

‘Should you find that the taking of Shreveport will occupy ten or fifteen days more time than General Sherman gave his troops to be absent from their command you will send them back at the time specified in his note of (blank date) March, even if it should lead to the abandonment of the main object of the expedition. Should it prove successful, hold Shreveport and Red River with such force as you deem necessary and return the balance of your troops to the neighborhood of New Orleans.’

These instructions, I was informed, were given for the purpose of having ‘all parts of the army, or rather all armies, act as much in concert as possible,’ and with a view to a movement in the spring campaign against Mobile, which was certainly to be made ‘if troops enough could be obtained without embarrassing other movements; in which event New Orleans would be the point of departure for such an expedition.’ A subsequent dispatch, though it did not control, fully justified my action, repeated these general views and stated that the commanding general ‘would much rather the Red River expedition had never been begun that that you should be detained one day beyond the 1st of May in commencing the movement east of the Mississippi.’

The limitation of time referred to in these dispatches was based upon an opinion which I had verbally expressed to General Sherman at New Orleans, that General Smith could be spared in thirty days after we reached Alexandria, but it was predicted upon the expectation that the navigation of the river would be unobstructed; that we should advance without delay at Alexandria, Grand Ecore, or elsewhere on account of low water, and that the forces of General Steele were to co-operate with us effectively at some point on Red River, near Natchitoches or Monroe. It was never understood that an expedition that involved on the part of my command a land march of nearly 400 miles into the enemy’s country, and which terminated at a point which we might not be able to hold, either on account of the strength of the enemy or the difficulties of obtaining supplies, was to be limited to thirty days. The condition of our forces, and the distance and difficulties attending the further advance into the enemy’s country after the battles of the 8th and 9th against an enemy superior in numbers to our own, rendered it probable that we could not occupy Shreveport within the time specified, and certain that without a rise in the river the troops necessary to hold it against the enemy would be compelled to evacuate it for want of supplies, and impossible that the expedition should return in any event to New Orleans in time to co-operate in the general movements of the army contemplated for the spring campaign. It was known at this time that the fleet could not repass the rapids at Alexandria, and it was doubtful, if the fleet reached any point above Grand Ecore, whether it would be able to return. By falling back to Grand Ecore we should be able to ascertain the condition of the fleet, the practicability of continuing the movement by the river, reorganize a part of the forces that had been shattered in the battles of the 7th, 8th, and 9th, possibly ascertain the position of General Steele and obtain from him the assistance expected for a new advance north of the river or upon its southern bank, and perhaps obtain definite instructions from the Government as to the course to be pursued.

Upon these general considerations, and without reference to the actual condition of the respective armies, at 12 o’clock midnight on the 9th I countermanded the order for the return of the train, and directed preparations to be made for the return of the army to Grand Ecore. The dead were buried and the wounded brought in from the field of battle and placed in the most comfortable hospitals that could be provided, and surgeons and supplies furnished for them. A second squadron of cavalry was sent, under direction of Mr. Young, of the engineer department, to inform the fleet of our retrograde movement and to direct its return, if it had ascended the river, and on the morning of the 10th the army leisurely returned to Grand Ecore.

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had been ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines that day (April 9, 1864), their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. According to Bates, after fighting off a charge by the troops of Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor, the 47th was forced to bolster the buckling lines of the 165th New York Infantry—just as the 47th was shifting to the left of the massed Union forces.

The regiment sustained heavy casualties during the Battle of Pleasant Hill. The regiment’s second in command, Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, was severely wounded in both legs. One of those wounds—an artillery shrapnel wound to his left leg near the ankle—resulted in a fractured leg. Regimental Color-Sergeant Benjamin Walls and Sergeant William Pyers both sustained gunshot wounds.

Color-Sergeant Walls, the oldest man in the regiment, was shot in the left shoulder as he was mounting the 47th’s flag on one of the Massachusetts artillery caissons that had been recaptured by the 47th. Sergeant Pyers was then shot while retrieving the American flag from Walls, thereby preventing it from falling into enemy hands. Both men survived and continued to fight for the 47th—Walls until his three-year term of service expired on September 18, 1864, Pyers until he was killed in action just over a month later during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia.

Many others were less fortunate. Hastily buried by comrades or local citizens, several still rest in unknown graves.

In addition, more men from the 47th Pennsylvania were captured and marched off to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, becoming the only soldiers from any Pennsylvania regiment to have men imprisoned there. At least three 47th Pennsylvanians never made it out alive; the remaining POWs were released in prisoner exchanges which took place from July through the fall of 1864.

Nearly two decades later, First Lieutenant James Hahn recalled his involvement (as a sergeant) in both engagements for a retrospective article in the January 31, 1884 edition of The National Tribune:

A PENNSYLVANIA SOLDIER’S EXPERIENCE.

Lieutenant James Hahn, of the 47th Pennsylvania infantry, writing from Newport, Pa., refers as follows to the engagements at Sabine Cross-roads and Pleasant Hill :

‘The 19th Corps had gone into camp for the evening about four miles from Sabine Cross-Roads. The engagement at Mansfield had been fought by the 13th Corps, who struggled bravely against overwhelming odds until they were driven from the field. I presume the rebel Gen. Dick Taylor knew of the situation of our army, and that the 19th was in the rear of the 13th, and the 16th still in rear of the 19th, some thirteen miles away, encamped at Pleasant Hill. They thought it would be a good joke to whip Banks’ army in detail : first, the 13th corps, then 19th, then finish up on the 16th. But they counted without their hosts; for when the couriers came flying back to the 19th with the news of the sad disaster that had befallen the 13th corps, we were double-quicked a distance of some four miles, and just met the advance of our defeated 13th corps – coming pell-mell, infantry, cavalry, and artillery all in one conglomerated mass, in such a manner as only a defeated and routed army can be mixed up – at Sabine Cross-roads, where our corps was thrown into line just in time to receive the victorious and elated Johnnies with a very warm reception, which gave them a recoil, and which stopped their impetuous headway, and gave the 13th corps time to get safely to the rear. I do not know what would have been the consequence if the 19th had been defeated also, that evening of the 8th, at Sabine Cross-roads, and the victorious rebel army had thrown themselves upon the ‘guerrillas’ then lying in camp at Pleasant Hill. It was just about getting dark when the Johnnies made their last assault upon the lines of the 19th. We held the field until about midnight, and then fell back and left the picket to hold the line while we joined the 16th at Pleasant Hill the morning of the 9th of April, soon after daybreak. It was not long until the rebel cavalry put in an appearance, and soon skirmishing commenced. About 4 o’clock in the afternoon the engagement become general all along the line, and with varied success, until late in the afternoon the rebels were driven from the field, and were followed until darkness set in, and about midnight our army made a retrograde movement, which ended at Grand Ecore, and left our dead and wounded lying on the field, all of whom fell into rebel hands. I have been informed since by one of our regiment, who was left wounded on the field, that the rebels were so completely defeated that they did not return to the battlefield till late the next day, and I have always been of the opinion that, if the defeat that the rebels got at Pleasant Hill had been followed up, Banks’ army, with the aid of A. J. Smith’s divisions, could have got to Shreveport (the objective point) without much left or hindrance from the rebel army.’

April 10-June 20, 1864:

After the regiment resettled in at Grand Ecore, Louisiana, 47th Pennsylvania scribe Henry D. Wharton finally had time to gather his thoughts and pen an account for the Sunbury American of the regiment’s recent battles:

Grand Ecore, Western La. }

April 12, 1864.DEAR WILVERT:–After lying over for three days at Natchitoches to recruit and get a fresh supply from the Commisariat [sic], we again pushed forward in hunt of the rebs, as the sequel will show, proved lucky to us, and a perfect discomfiture to the enemy. On the first days march we were detained several hours by letting the 13th Army Corps pass by us, when we pushed forward to Double Bridges, a distance of sixteen miles. It was at this place, shortly before our arrival that a brisk skirmish came off between our cavalry and the rebs, in which we lost ninety men in killed and wounded. The rebs loss was more severe, besides a number of prisoners. On our march next day we saw unmistakeable [sic] evidence of hot work, the limbs were knocked from trees and their trunks were well pierced with shot and a number of horses lie dead by the road side, which showed the good work done by our cavalry…. We made Pleasant Hill that day and encamped. It was here that we expected a heavy fight, but there was a mere skirmish, the rebs skedaddling in a hurry, followed by our cavalry. Our forces moved early next morning, the 13th corps far in the advance. We made but seven miles and then went into camp, when the news [broke] that the 13th and cavalry had engaged the enemy in force. Receiving two days hard tack, orders came to forward, which was done in double quick, making the distance, eight miles, in one hour and twenty minutes. We reached there at the right time, for the 13th had fought hard, expending their ammunition; the cavalry were repulsed and in their retreat made such confusion among the teams, that had it not been for our timely arrival, a panic would have ensued, exceeding that of Bull Run.

Our corps, the 19th, rushed to the rescue, fell into line of battle, and were soon pouring on the rebs a fire which turned the tide of affairs. We were two hours under fire, giving the enemy more than we received, when darkness caused the fight to come to a close, not, however, until we gave them a parting salute of two volleys from the whole corps. Three pieces of Nimm’s battery was [sic] captured by the enemy before our corps got there, besides the train of the cavalry, with ammunition and stores.

About 10 o’clock that night our forces made a retrograde movement, falling back to Pleasant Hill, to secure a better position.– The trains were sent back so as not to interfere with our movements. We arrived safely at nine o’clock, next morning [10 April 1864], and immediately prepared for the coming work. An hour later the rear guard came in informing us of the approach of the enemy.– Our skirmishers of cavalry and infantry were sent out, and ’twas not long until shots were exchanged. At this time, 10 o’clock, Smith’s 16th Army Corps reinforced us, and was soon formed in line of battle. Skirmishing continued until four o’clock, when the rebs commenced feeling our lines, with artillery, on right, left and centre [sic]. This was well replied to by the 25th N.Y. Battery. (The Battery to which Dad Randels and some others of our own boys are attached.)

The battle then commenced in real earnest. The rebs charged our lines, with cheers, firing volleys of musketry that would seem to annihilate our forces. They tried to flank our right and left, but the boys repulsed them handsomely. Batteries were captured and recaptured; advances were made and repulsed, the enemy fighting as though it was the last of a desperate cause. Our volleys of musketry, of which more was used than in any fight during the war, and the executions of the artillery was too much for them, for they fled, our men after them, yelling shouts of victory, and chasing them for five miles beyond the battlefield. Our fire told with terrible effect. A rebel Lieut.-Col. prisoner, said that in a charge made by one of their Brigades, when they advanced so far as to make a capture of a portion of our left a sure thing, they were met by a fire that destroyed four hundred, and then were driven back in confusion. In another advance, our fire was so destructive that only three men were left unscathed to return within their lines.

The prisoners captured amounted to two thousand; among them one General, one Lieutenant-Colonel, and any quantity of Captains and Lieutenants. Of the number killed and wounded I am unable to say, but the general impression is it amounted to over five thousand. The dead body of Lieut.-Gen. Mouton was found on the field, they leaving him in their hasty retreat. He was killed by the explosion of a shell, tearing away the upper portion of his head.

Nimm’s Battery was recaptured by our regiment. Twenty-three pieces of artillery were captured by the enemy. It was at the recaptured of Nimm’s Battery that our Color Sergeant, B. F. Walls, received his wound. The Squire was so well pleased at the recapture, that he rushed forward with his flag and raised it on the wheels of a caisson, when he fell pierced by a bullet in the left shoulder.

It seems the enemy were panic stricken, fleeing from the field in confusion, not caring for the wounded. They burned their entire train for fear of its falling into our hands. Part of this was well for us, for by doing so, the train taken from our cavalry was destroyed, giving us the satisfaction that our stores done [sic] them no good.

Our whole loss, in killed, wounded, missing and stragglers is estimated at three thousand. The greatest portion belonging to the 13th corps, having occurred at Sabine, on the 8th, in the first fight. The loss in Company “C,” is Jeremiah Haas, killed. Jerry felt no pain, dying almost instantly. He was beloved by his comrades, and his loss is much regretted by them. He was a good soldier, a young man whose morals were not injured from the influences of an army, and best of all, an honest man. The wounded are –

Serg. Wm. Pyers, arm and side, not dangerous.

” B. F. Walls, left shoulder.

Private Thomas Lothard, two wounds in arm, slight,

” Cornelius Kramer, left leg, below knee.

” George Miller, side.

” Thomas Nipple, hip, slight.

” James Kennedy, right and side, severe.Missing – J. W. McNew, J. W. Firth, Samuel Miller, Edward Matthews, John Sterner and Conrad Holman.

The whole force of the enemy was thirty-five thousand – ten thousand of them coming fresh into the fight on the second day, at Pleasant Hill, under General (Pap) Price. Our forces, parts of the 19th and 16th corps, amounted to fifteen thousand, the 13th taking no part in this action. We expect to have another fight soon, probably at Shreveport, where it is expected the rebellion will be crushed on the western side of the Mississippi.

Our wounded are getting along finely, and are in the best of spirits. They will be sent to New Orleans to remain in hospital until convalescent. The boys remaining are well and seem anxious for another encounter with the graybacks.

The 47th Pennsylvanians remained at Grand Ecore for a total of eleven days (through April 22, 1864), where they engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications in a brutal climate. They then moved back to Natchitoches Parish where they arrived in Cloutierville, after marching forty-five miles, at 10 p.m. that night. En route, the Union forces were attacked again—this time in the rear, but they were able to quickly end the encounter and continue on.

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were stationed just to the left of the “Thick Woods” with Emory’s 2nd Brigade, 1st Division for the Battle of Cane River Crossing at Monett’s Ferry, Louisiana, April 23, 1864 (Union Army map, public domain).

The next morning (April 23, 1864), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight.

As part of the advance party led by Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on the Confederate cavalrymen commanded by Brigadier-General Hamilton P. Bee in the Battle of Monett’s Ferry (also known as the “Cane River Crossing” or the “Affair at Monett’s Ferry”).

Responding to a barrage from the Confederate’s twenty-pound Parrott guns and raking fire from enemy troops situated near a bayou and on a bluff, Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederates busy while sending the other two brigades to find a safe spot where his Union troops could ford the Cane River.

Affair at Monett’s Bluff, Louisiana, April 23, 1864 (Major-General Nathaniel Banks’ Red River Campaign Report, public domain).

As part of the “beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvanian Volunteers supported Emory’s artillery.

Meanwhile, other troops who were part of Emory’s command found and worked their way across the Cane River, attacked Bee’s flank, and forced a Rebel retreat. That Union brigade then erected a series of pontoon bridges, enabling the 47th and other remaining Union troops to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day.

As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners.

Encamping overnight before resuming their march toward Rapides Parish, the 47th Pennsylvanians finally arrived on April 26 in Alexandria, where they camped for seventeen more days (through May 13, 1864).

While there, they engaged yet again in the hard labor of fortification work, and also helped to build “Bailey’s Dam,” a timber structure that enabled Union gunboats to make their way back down the Red River.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” in reference to the Union officer who oversaw its construction, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated Union gunboat passage (public domain).

In a follow-up letter penned from the 47th’s encampment at Morganza to the Sunbury American on May 29, 1864, Henry D. Wharton reported on the dam’s construction and other key details from this difficult period of service:

MORGAWZA BEND [sic, Morganza], La., May 29, 1864

DEAR WILVERT: – The uncertainty of a mail passing the blockade on the Red river, established by the Johnny Rebs while we were lying at Alexandria, prevented me from writing to you until now; but knowing the anxiety you have for us, I feel justified in commencing from where I dated my last letter, and will give you the ‘dangers we have passed’ as I recollect them.

Our sojourn at Grand Ecore was for eleven days, during which time our position was well fortified by entrenchments for a length of five miles, made of heavy logs, five feet high and six feet wide, filled in with dirt. In front of this, trees were felled for a distance of two hundred yards, so that if the enemy attacked we had an open space before us which would enable our forces to repel them and follow if necessary. But our labor seemed to the men as useless, for on the morning of 22d April, the army abandoned these works and started for Alexandria. From our scouts it was ascertained that the enemy had passed some miles to our left with the intention of making a stand against our right at Bayou Cane, where there is a high bluff and dense woods, and at the same attack Smith’s forces who were bringing up the rear. This first day was a hard one on the boys, for by ten o’clock at night they made Cloutierville, a distance of forty-five miles. On that day the rear was attacked which caused our forces to reverse their front and form in line of battle, expecting too, to go back to the relief of Smith, but he needed no assistance, sending word to the front that he had ‘whipped them, and could do it again.’ It was well that Banks made so long a march on that day, for on the next we found the enemy prepared to carry out their design of attacking us front and rear. Skirmishing commenced early in the morning and as our columns advanced he fell back towards the bayou, when we soon discovered the position of their batteries on the bluff. There was then an artillery duel by the smaller pieces, and some sharp fighting by the cavalry, when the ‘mule battery,’ twenty pound Parrott guns, opened a heavy fire, which soon dislodged them, forcing the chivalry to flee in a manner not at all suitable to their boasted courage. Before this one cavalry, the 3d Brigade of the 1st Div., and Birges’ brigade of the second, had crossed the bayou and were doing good service, which, with the other work, made the enemy show their heels. The 3d brigade done some daring deeds in this fight, as also did the cavalry. In one instance the 3d charged up a hill almost perpendicular, driving the enemy back by the bayonet without firing a gun. The woods on this bluff was so thick that the cavalry had to dismount and fight on foot. During the whole of the day, our brigade, the 2d was supporting artillery, under fire all the time, and could not give Mr. Reb a return shot.

While we were fighting in front, Smith was engaged some miles in the rear, but he done his part well and drove them back. The rebel commanders thought by attacking us in the rear, and having a large face on the bluffs, they would be able to capture our train and take us all prisoners, but in this they were mistaken, for our march was so rapid that we were on them before they had thrown up the necessary earthworks. Besides they underrated the amount of our artillery, calculating from the number engaged at Pleasant Hill. The rebel prisoners say it ‘seems as though the Yankees manufacture, on short notice, artillery to order, and the men are furnished with wings when they wish to make a certain point.

The damage done to the Confederate cause by the burning of cotton was immense. On the night of the 22d our route was lighted up for miles and millions of dollars worth of this production was destroyed. This loss will be felt more by Davis & Co., than several defeats in this region, for the basis of the loan in England was on the cotton of Western Louisiana.

After the rebels had fled from the bluff the negro troops put down the pontoons, and by ten that night we were six miles beyond the bayou safely encamped. The next morning we moved forward and in two days were in Alexandria. Johnnys followed Smith’s forces, keeping out of range of his guns, except when he had gained the eminence across the bayou, when he punished them (the rebs) severely.

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gunboats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people, will eat) so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the ironclads down the river. After a great deal labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’

Tragically, sometime after the 47th’s departure from Alexandria, an individual or groups of individuals torched the city. Although many present-day historians indicate that this terrible act was the work of Union troops, Henry Wharton recounted in his same letter of May 29 what had been reported about the fire to leaders of the 47th on May 14, 1864, and also provided a glimpse into two horrific attacks by Confederates on non-combatant ships:

The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order the day before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits [sic] on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gunboat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

As the Union troops continued their march toward the southeastern part of Louisiana, they passed Fort DeRussy, and then engaged in yet another battle—this time in Avoyelles Parish near Marksville. Fighting in this Battle of Mansura on May 16, 1864, Union infantry skirmished with Dick Taylor’s Confederates, and then orchestrated a flanking attack to force Taylor’s troops into retreat during what was largely a four-hour artillery shoot out:

On Sunday, May 15, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad wherewith the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. – We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed in line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired and we advanced ‘till dark, when the forces halted for the night, with orders to rest on their arms. – ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee. Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, the infantry advanced in line until they reached Mousoula [sic], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain correctly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport on the Achafalaya [sic] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over. – The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of our army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.

On Saturday, May 21, 1864, Brigadier-General William Emory then ordered the men of Company C – the 47th Pennsylvania’s Color-Guard Unit—to move enemy prisoners to a safer Union stronghold. So, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin and his men marched one hundred and eighty-seven Confederate soldiers south, transferred their management to the appropriate Union authorities, and returned to the regiment.

In his continuation of his May 29 letter, Henry Wharton delivered the sad news that James Kennedy had died at a Union hospital in New Orleans from the wounds he had sustained in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill on April 9:

His friends in the company were pleased to learn that Dr. Dodge of Sunbury, now of the U.S. Steamer Octorora, was with him in his last moments, and ministered to his wants. The Doctor was one of the Surgeons from the Navy who volunteered when our wounded was [sic] sent to New Orleans.

Aftermath

In addition to deaths in combat or at Confederate prison camps, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers lost a significant number of men to disease and the hardships wrought by hard duty in a difficult climate. Three members of the regiment also drowned during the Red River Campaign—one at the start of the expedition, the other two as the regiment’s time in Louisiana wound down.

Many of the regiment’s dead were ultimately laid to rest at the Chalmette National Cemetery in Chalmette, Louisiana—a fair number in unmarked graves. The graves of others still have not yet been located. At least one historian believes the missing status of soldiers on both sides is due to a combination of factors—poor military record keeping, hasty burials of war dead by civilians or retreating troops in shallow, unmarked graves, or the destruction of bodies by feral hogs which devoured soldiers’ remains before they could be properly interred. Quite simply, the scale of the carnage, once again, had overwhelmed military leaders on both sides.

History books record the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield as a Confederate victory, the Battle of Pleasant Hill as a technical victory for the Union, and the Battle of Monett’s Ferry/Cane River Crossing and Battle of Mansura/Marksville as clear victories for the Union.

Through it all, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania was represented by just one regiment—the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Sources:

1. 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Records, in Camp Ford Prisoner of War Database. Tyler, Texas: The Smith County Historical Society, 1864.

2. A Pennsylvania Soldier’s Experience, in Up the Red River: How the Famous Banks Expedition Came to Grief: Off for Shreveport: The March from Grand Ecore to Pleasant Hill: Sabine Cross-Roads, And the Part the 13th Corps Played in That Battle. Washington, D.C.: January 31, 1884.

3. Banks, Nathaniel P. “General Banks’s Report of the Red River Campaign,” in Annual Report of the Secretary of War, in Message of the President of the United States, and Accompanying Documents, to the Two Houses of Congress, at the Commencement of the First Session of the Thirty-Ninth Congress. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1866.

4. Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

5. Burial Ledgers, in Records of The National Cemetery Administration, and in Records of the U.S. Departments of Defense and Army (Quartermaster General). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, 1864-1865.

6. Civil War Muster Rolls, in Records of the Department of Military and Veterans’ Affairs (Record Group 19, Series 19.11). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

7. Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

8. Claims for Widow and Minor Pensions, in U.S. Civil War Widows’ Pension Files. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives.

9. Dixon, Boyd. Archaeological Investigations at the Third Phase of the Battle of Mansfield, in Bulletin of the Louisiana Archaeological Society, Number 33. New Orleans, Louisiana: 2006. Retrieved online December 2015.

10. Gilbert, Randal B. A New Look at Camp Ford, Tyler Texas: The Largest Confederate Prison Camp West of the Mississippi River, 3rd Edition. Tyler, Texas: The Smith County Historical Society, 2010.

11. Interment Control Forms, in Records of the U.S. Office of the Quartermaster General. College Park, Maryland: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

12. Joiner, Gary D. The Red River Campaign: March 10—May 22, 1864. Civil War Trust: Washington, D.C.. Retrieved online December 2015.

13. Registers of Deaths of Volunteers, in Records of the U.S. Adjutant General’s Office. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, 1864-1865.

14. Reports of Maj. Gen. N. P. Banks (dated April 6, 1865), et. al., in The War of the Rebellion, Vol. XXXIV: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1891.

15. Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

16. “The Red River Campaign: Detailed Account of the Retrograde Movement How the Gunboats Escaped.” New York, New York: The New York Times, 5 June 1864.

17. Wharton, Henry D. (as “H. D. W.”). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 1864-1865.

You must be logged in to post a comment.